Time Magazine Talks with Will Wright

"Everything from the size of your Sim's feet to hair accessories will be customizable."

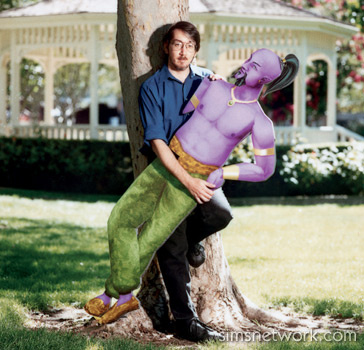

GENIUS AT PLAY: Wright clings to one of his Sims creations near his California offices

Reinventing the Sims

Will Wright hopes to erase some bad memories with a new version of the best-selling computer game

By Chris Taylor

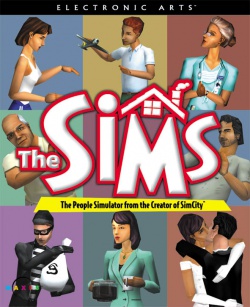

In the beginning—that is, in 1989—Will Wright created Sim City. And it was good. Millions of PC owners got hooked on the game's godlike powers that let players create a town, fill it with enough parks and police stations to please an unseen population, and watch the town grow. Then in 2000 Wright said, "Let there be life." And he created The Sims, which let players micromanage the lives, loves and careers of adorable little people (called "Sims") who lived in homes reminiscent of the Cleavers' in the simpler era of black-and-white television. The Sims shipped 8 million copies, becoming the best-selling computer game of all time. For Wright, it was all very good.

As the 21st century dawned, Wright reigned as the undisputed deity of the PC-game world. That is, until his next big thing: The Sims Online, in which players from all over the world let their little people roam and mingle in a vast virtual environment. It sounded like the Garden of Eden. And lo, it was a boring, poorly populated bomb. Gamers suddenly realized that Wright was not infallible after all.

So what's next for this unflappable 43-year-old geek whose brain seems to overflow with ideas? Since The Sims Online debacle, he has been back at his virtual drawing board, sketching out a new breed of Sims. They look cooler, sound clearer and inhabit homes that are less Leave It to Beaver and more Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Most audacious of all, they have real lives: they are born, they grow up, give birth and die. Legions of fans await the result, The Sims 2, due for release in February. Will it be a return case of divine inspiration—or will Wright slip again? His reputation rests on the outcome—as does the computer-game industry's best hope for the mainstream recognition it craves.

Wright is a gaunt, wiry figure with large glasses and a perpetual ironic smirk. His wardrobe seems to consist pretty much of gray shirts and black jeans. He is soft-spoken and reserved, with a playfulness just beneath the surface. At this year's Electronic Entertainment Expo in Los Angeles, the biggest date on the computer-game industry's calendar, Wright casually slipped reporters near worthless Argentine banknotes as a surreal bribe. In his office at Maxis, his Walnut Creek, Calif., company, he is a nervy, perpetual-motion machine, methodically pulling apart glow-in-the-dark Silly Putty or constructing towers out of magnetic plastic toys.

Wright, in other words, is obsessed with creating things. As a child in Atlanta, that meant balsa-wood planes and train sets. When he discovered computers, it meant digital cities. These days it often means building battle robots with his 17-year-old daughter or inventing a special set of toy building blocks, which he calls Architex, that can be used to design houses. Indeed, it is his love for architecture that has led Wright to his greatest success. When the Sims germinated in his mind, it was like a virtual version of Architex. You built a home, then computer people called Sims moved in and told you whether they liked it or not. The original game was called Doll House, and teenage boys in a focus group rated it the worst idea they had ever heard.

But Wright persisted. Eventually The Sims became less of an afterthought to house building and more the focus of the game itself. Soon each Sim had a realistic set of needs represented by bars on the screen that turned from green to red. When a Sim registered as hungry, for example, it was time to point him toward the fridge (assuming you had bought him one).

The objective was to keep the Sims' needs fulfilled so they could get promotions and raises when they went to work or buy more stuff to meet their needs faster. Like a lot of Wright's work, it was all very tongue in cheek. The Sims were caricatures who never aged (neither did their children, who arrived as if by stork). The products you bought for them got ever more expensive and outrageous (like the Love-o-matic vibrating bed), and the chirpy 1950s movie music enhanced the Cleavers feel. Somehow it all worked.

Players found it easy to invest their imagination in the Sims' lives, with their carefully constructed needs, personalities and relationships. After the game was released, more than 1,000 fan websites sprang up in which players posted screen shots from their Sims' world. After the runaway success of the original, Wright supplied ever more storytelling tools. Six expansion sets—the Sims have pets! the Sims go on hot dates!—sold 6.8 million copies. (The seventh and final expansion, Makin' Magic, is to be released this Halloween.)

The stumble that was The Sims Online happened in late 2001. It was an Internet-based Sims world in which the storytelling was supposed to come from the interactions among players. It didn't gel. Fewer than 100,000 subscribers signed up to pay $10 a month for the service, far fewer than Maxis' hopes. Making your Sims mingle as if at a global cocktail party was, it turned out, not as addictive as trying to win them a promotion or building them a new bathroom. "The Sims Online was a wildly optimistic view of people providing their own entertainment," says Dan Morris, executive editor of PC Gamer magazine. "They needed a game with a well-defined narrative, not just a sandbox." Wright had effectively abdicated responsibility for the parameters of possible storytelling. The Sims is Wright's world; we just play in it.

For The Sims 2, Wright has learned his lesson—and then some. The narrative arc of the game has gone epic. Whereas the original Sims were as timeless as cartoon characters, their successors go through five distinct ages, from baby to senior—not quite the full Shakespearean seven but close enough. You used to have to try quite hard to kill Sims; now old age will get them in the end. The Sims 2 revolves around Big Life Moments that will positively or negatively affect each Sim's final score when he or she dies: successful potty training, the first kiss, the death of a parent, marriage, divorce. What was formerly a slice of family life becomes a tale of generations—or, as Wright puts it, more like a James Michener novel.

The richness of potential plot lines is matched by the Sims' sumptuous new look. The game's graphics, especially the lighting and the characters' facial features, are way ahead of what was possible in 2000. Everything from the size of your Sim's feet to hair accessories will be customizable. Wright found that a lot of players wanted to turn their Sims into virtual copies of their families and friends. Not only will that be possible, but also at the click of a button you will be able to see a random selection of children that any two Sims' genetic traits might produce.

All this is a long way from the virtual dollhouse Wright originally had in mind. What nobody in the industry can say for now is whether he has strayed too far. The casual gamers who fell in love with The Sims included many youngsters who became aware for the first time of what it was like to be in charge of little people who wouldn't stop watching TV and go to bed. Will those same players really care to see their Sims grow old and die? Will the enhanced realism of diaper changing gross them out?

The answers matter to the computer-game industry, which needs more hits of this kind if it is ever going to widen its appeal beyond the 3 million hard-core gamers (mostly men in their teens and 20s) who typically buy a game a month. As with The Sims Online, expectations are high: this is a business in which sequels often do better than the original. (Wright has one other game in the works—which he isn't able to talk about—tentatively titled SimEverything, in which players start out by bonding molecules and end up building galactic civilizations.) "The Sims is a dream franchise for people who want to see the medium grow," says Morris. We'll find out soon enough. And if it doesn't work out—well, Wright can always try releasing Architex.